What is the risk #

The EU Commission’s research center (JRC) investigated in spring 2021 in a report and concluded that the terrorist risk of nuclear power is vanishingly small, and that even successful terrorism will have relatively insignificant consequences. JRC, finds that hydropower/dams and oil and gas infrastructure pose a significantly greater terrorist risk, although this is still an extremely unlikely hypothetical scenario [1].

The Swedish Civil Contingency Agency (MSB) has prepared risk assessments for the various accidents that nuclear power and hydropower can be affected by [2].

They assess the risk of a serious nuclear accident is considered to be very low, approx. 1 in 10,000 years. In addition, the safety at the Swedish nuclear power plants is assessed to be so good that no one will suffer acute radiation damage, even in the event of a worst case accident (INES-7). It is noteworthy in the MSB’s report that, for example, hydropower plants are estimated to have a significantly higher accident risk with approx. 1 in 500 years.

Airplane crash scenario #

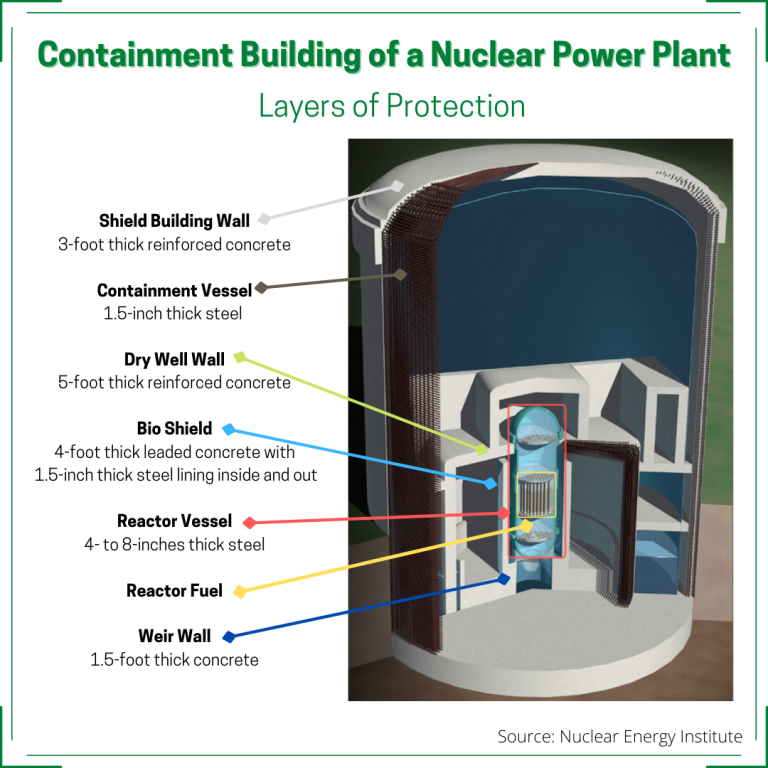

The construction of the plants is among the most robust industrial facilities ever built. The reactor vessel holding the fuel is made of steel more than a foot thick. The reactor building is made of reinforced concrete. All the equipment and piping are ruggedly constructed, and any equipment not located in the reactor building is housed in areas that are also strongly built. Furthermore, the fuel itself is encased in a solid metal alloy that is difficult to breach.

To give an idea of how tough this material is, Sandia National Laboratories in 1988 crashed an F4 Phantom jet into the same sort of reinforced concrete that is used to construct nuclear power plants. The result: the jet was obliterated, and the concrete was more or less fine. The worst scar was less than 2.5 inches deep [3].

In 2002, the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) undertook an advanced computer modeling study to determine if nuclear power plants could withstand the impact of an aircraft crash, similar to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The Boeing 767 was selected as the crash aircraft in the study because its weight is more substantial than almost all commercial jet airliners flown in the U.S [4].

The study chose a target location on the grounds of a nuclear power plant in which the most damage would occur if an aircraft struck it. The angle of attack was chosen to be perpendicular to the centerline of the structures, which would maximize the force of the plane. The study also considered an aircraft speed that would allow the pilot to control the aircraft accurately. Indeed, the speed chosen was the same as that of the airplane that hit the Pentagon.

The study concluded that none of the parts of the Boeing 767 — including the engine, fuselage, wings, or even jet fuel — could enter the containment building or any other sensitive areas, like the used fuel storage pool. This means that in the ultimate catastrophic event — an airline crash or missile strike — a U.S. nuclear power plant would not leak radiation.

Additionally, because of their size (which is relatively small compared to a target like the World Trade Center or Pentagon), nuclear power plants are more difficult to damage, as it is challenging to aim the aircraft to hit the structure at its most damaging point. Used fuel is located underground and is not visible to a pilot from outside the plant. Moreover, other intervening structures on the power plant site make it almost impervious to an aircraft strike.

Indside terrorism #

Let’s assume that terrorists get inside a nuclear reactor, close to the radioactive fuel, and detonate a bomb there. What happens?

If they’re extremely lucky and professional (how do they access the fuel?!), the fuel explodes, falls down, and that’s it. It remains contained in the facility. They would need to blow up the entire reactor and its containment enclosure for radioactive material to escape.

Even if they did, the radioactive material would be limited to the blast of a traditional bomb. Engineers in the control room could quickly stabilize the situation.

Bombing the reactor would not work. They would need to engineer a meltdown, stop all the active measures against it, and physically change the design of the plant. It would be easier to shut down the entire electric grid of a country like the US than engineer a nuclear meltdown

Cyber attack #

Nuclear plants are still mostly analog. The safety and control systems and other vital plant components are not connected to business networks or the Internet. Also, nuclear is more monitored than any other industry. The nuclear industry does not use firewalls to isolate these systems, that’s not good enough. The plants use hardware based data diode technologies developed for high assurance environments, like the DOD. Data diodes allow information to be sent out, like operational and monitoring data, but ensure that information cannot flow back into the plant [5].

In 2014, anti-nuclear group began releasing information it had hacked from a South Korean company that operates several nuclear power plants, demanding that the company take their nuclear plants offline by Christmas. Or else! [6].

But the only problem is that there was nothing important hacked at the plant so their threats were toothless. Releasing personnel files and business data may, again, be embarrassing, but it doesn’t compromise nuclear safety, and doesn’t lend itself well to blackmail.

Sources #

- https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/business_economy_euro/banking_and_finance/documents/210329-jrc-report-nuclear-energy-assessment_en.pdf

- https://www.stralsakerhetsmyndigheten.se/om…/ines-skalan/

- https://interestingengineering.com/crashed-jet-nuclear-reactor-test

- https://www.nrc.gov/docs/ML0412/ML041200200.pdf

- Is Hacking Nuclear Power Plants Something We Should Be Afraid Of? (forbes.com)

- http://www.forbes.com/sites/jamesconca/2014/12/24/hacking-of-south-korean-nuclear-reactors-poses-no-danger/